You've heard of it. You've wondered about it. You've seen films of the classic ones on laserdiscs, VHS tapes and new-fangled DVDs. If you're really lucky (or live in the U.K.) there's a reasonable chance you've even attended one of them. It appears, astounds, leaves a distinct impression, then bounces back again. It's The Secret Policeman's Ball: the comedy, music and variety pageant in support of Amnesty International. It's been happening in various incarnations since 1976, and this Sunday -- for the first time in America, in New York City, and in fact for the first time ever outside of London -- it happens in an all-new production for 2012.

For those who don't have tickets -- the show will be streaming for free in the U.S.A. on Epix HD. And will eventually I'm sure come to all of us on DVD.

The large, noteworthy cast of the new show this Sunday night at Radio City Music Hall will feature funny women (Sarah Silverman, Kristen Wiig, Rashida Jones), funny men (Jon Stewart, Russell Brand, Eddie Izzard, Seth Meyers, Andy Samberg, a slew of SNL-ers, and Burmese comedian Maung Thura Zarganar), and popular musical combos with funny names but who aren't necessarily funny (Coldplay, Mumford & Sons). Even Muppet curmudgeons Statler and Waldorf will opine on the antics of the all-star cast -- and I saw those two foam-based kvetchers in the first-ever live Muppet Show in 2001 for Save the Children (featuring Brooke Shields as Miss Piggy!), so despite their surly nature, even they know a good benefit show. And that's exactly what the Secret Policeman's Ball is, really: the grandfather of the wildly entertaining modern charity pageant.

With this in mind, I thought it would be instructive to delve back in time, to examine the origins and evolutions of the Secret Policeman's Ball. I found the ideal source and subject in producer, writer, humorist, bon vivant, film-festival curator, Mod, Rocker, Mocker and impresario Martin Lewis.

Over the past dozen years, Mr. Lewis has produced and hosted (in Los Angeles, New York and Washington DC) some of the finest pop-cultural events and entertainments I've ever attended. Looking back through my reviews and notes I am reminded of evenings saluting a very wide range of subjects: Including the Beatles, John Lennon, Bob Dylan, Jimi Hendrix, the Who, Otis Redding, Nick Drake, The Police, Paul McCartney, the 40th anniversaries of the 1967 Monterey Festival and the 1969 Isle Of Wight Festival, the 40th anniversary of the Monkees film Head, the 50th anniversary of Blackboard Jungle, Stephen Frears, Glenn Ford, Monty Python, even a filmic event honoring NASA and Buzz Aldrin. The eclectic list goes on and on; frankly, the man blows minds. It's not for nothing that the magazine L.A. Weekly once described Lewis as a Renaissance Man. Way back in time he was a co-producer of the very first Amnesty charity shows with ?ber-funnyman John Cleese and others.

Lewis came of age in the late 1960s and early 1970s first as a music journalist, and subsequently as a publicist mentored by the late Beatles press agent Derek Taylor. Which means that he had to have been quite young at the time he found himself helping produce that first Amnesty show in 1976. "I was about three years old then..." he offers me "... evidently I was a child prodigy as a producer!" This is absolutely accurate, give or take a couple of decades. He then giggles and relents, admitting that he was "actually 23 at the time, which makes me very old indeed now." Lewis happens to have been a participant in some of the most fascinating projects in modern entertainment and has a phenomenal memory with instant recall of gargantuan amounts of detail about the events and personalities in his experience. He also has a historian's obsession for detail about pop-culture that preceded him. In short -- he gives "good witness"...

"Amnesty first started doing these fund-raising shows in 1976," Mr. Lewis clarifies beyond any question. "The instigation came from John Cleese who wanted to help out. And he did it in the only way he knew how. Which was to put on a show with what he described as 'a few friends'. Who of course transpired to be his colleagues in Monty Python and other luminaries of British comedy."

Though he initially volunteered his services to Amnesty just in the recording of a live album (having embarked on comedy record production the previous year with a satirical album lampooning Idi Amin) and providing his services to help publicize and market the show, Mr. Lewis quickly found himself helping in the production of the show:

There were some terrific folks working at Amnesty U.K. in those days particularly Peter Luff and David Simpson who took the lead. But it became an all-hands-on-deck production. None of us had really had experience of producing a live stage show on that scale. I'd co-produced a concert at the Royal Albert Hall in 1974, so I had a bit of production background. But everyone just chipped in. And somehow it all worked out. Peter Luff is the guy who should get the most credit for the first two shows. And another Amnesty staffer called Peter Walker was absolutely instrumental in the 1979 and 1981 shows. Those two chaps are the under-sung heroes.

The show itself was an assembly of the cream of Post-War, Baby-Boomer British comedy," he elaborates. "It swept back in time to the Beyond the Fringe troupe, through Monty Python, and a (practically-unknown-in-America) comedic trio called The Goodies. All three groups emerged from the British university spheres of Oxford and Cambridge -- known colloquially as Oxbridge.

"If you went to university at Oxford or Cambridge in the late 1950s or early 1960s -- comedy was a big side interest. Of course just like with American college-goers -- some students were interested in being jocks. But those with a comedic bent were drawn to writing and performing. So you went and performed late at night at events that were called "smokers" -- mainly because people smoked so much at them," e laughs, reflecting on the revues in that distant time in history when people actually smoked.

These anarchic events Mr. Lewis describes as the British equivalent of the U.S. comedy club boom of the '70s and '80s, and he clarifies further still: "It was an enjoyable digression from your university studies. You didn't go to Oxford or Cambridge to study to be a comedian. You went there as part of the process by which you would emerge as an economist, lawyer or doctor. But in exploring their muse just as a hobby, many students discovered that they were gifted in comedic writing and performing. Lo and behold, in the early 1960s, there was this sizable wave of young people who discovered that they had -- in the words of Noel Coward -- a talent to amuse."

"The first famous manifestation of this was at the 1960 Edinburgh Festival," he continues, "where they had the official festival for high arts, and the unofficial sideshow of student revues and entertainments that were dismissively dubbed the Fringe Festival. Beyond the Fringe was actually staged by the serious mainstream festival to counter the Fringe Festival... Rather like an official bootleg. That was the origin of the title Beyond the Fringe. An impresario named Willie Donaldson simply grabbed the two best performers from Oxford and the two best from Cambridge, and stuck them together and said, 'Write and perform a show.' So successful was Beyond The Fringe at the Edinburgh Festival that it transferred to the West End of London."

"Then it became a comedy gold-rush. Rather like the London-based record company A&R men who all flocked to Liverpool in the wake of the Beatles' success to see if there were other pop groups on Merseyside. Almost fully-grown West End impresarios flocked to the Edinburgh Festival looking to see if there was anything else "Beyond the Fringe." The next show imported to the West End was another Oxbridge revue titled Cambridge Circus, which featured Cleese and various performers from the next generation; and by 'the next generation,' I'm talking about an entire two years later! John Cleese had been at university just two years behind Peter Cook, and had seen him at smokers, and was in awe of him."

Cook fandom is easy to understand -- behold Bedazzled ("You fill me with inertia.") -- and here let us segue briefly to the immediate present. Mr. Lewis, who's no slouch at comedy himself and has worked with the best in the business, leaps to laud one of the participants in this year's show -- Russell Brand: "Russell has a fierce intelligence. He understands the zeitgeist of fame and celebrity. He understands what it's about. Of all the comedians who've come out of Britain in the last twenty years, there is nobody who would be more appreciated by Peter Cook than Russell Brand. Peter would have loved Russell. I can't bestow a higher honor on him than that."

Mr. Lewis continues the long and fascinating tale of the modern comedy pageant's development by explaining how many of those comedy upstarts in their early twenties were then hired by the BBC to create and produce a plethora of radio and television programs. Foremost among the hires: the comedic magpie David Frost. Yes, as in Frost/Nixon. As in The Frost Report. Frost rose in the space of just five years to become a host and producer with his own powerful production company. Apparently a Lorne Michaels before there was a Lorne Michaels. Practically every one of the emerging comedy generation coming out of Oxbridge in the 1960s at one time or other ended up writing for... performing for... and/or being semi-benignly exploited by the ubiquitous Mr. Frost.

Frost had intentionally NOT been invited to be a participant of the upcoming 1976 Amnesty gala -- yet practically all the cast had at some point written for, performed for, been semi-benignly exploited by the aforementioned Frost. A situation that prompted John Cleese to give the impending benefit show the tongue-in-cheek working title of An Evening Without David Frost. Cleese finally named that inaugural gala A Poke in the Eye (with a Sharp Stick)

The richness of this strain of history proves complex enough to fill a long book -- perhaps Mr. Lewis will honor us with one -- and additionally what's funny here is that all of this and more has sprung from my simple question, paraphrased: How'd this show get its weird yet memorable title? We continue.

Lewis himself is the master of digression and divertissement. Each recollection he shares prompts him to offer up yet another nugget of completely tangential but fascinating information. Such as his memory of how Peter Cook responded to people who fawned over his brand of satire. Cook apparently would say that it was indeed modeled on "those wonderful satirical Berlin cabarets of the late 1920s... that did so much to stop the rise of Hitler and prevent the outbreak of the Second World War..."

So how did the Secret Policeman's Ball get its title? It takes a visionary. Despite the initially somewhat rough-hewn nature of the first Amnesty benefit -- which Mr. Lewis fondly recalls as being held on three successive evenings, late at night, in a proper theatre (vacated after some regular West End entertainment) with a "pleasantly lubricated" cast, crew and audience, plus an energy roughly equivalent to the concurrent wave of punk-rock (without the gobbing) -- at the time wearing his Amnesty publicist hat, Lewis dubbed that first show as being the British comedic equivalent of George Harrison's 1971 Concert for Bangladesh. Harrison's show having been an inspiration to Lewis and many of Harrison's pals in Monty Python.

(This week Amnesty has released the music video for Evan Rachel Wood's charity recording of the Bob Dylan-George Harrison writing collaboration I'd Have You Anytime, produced by the same Mr. Lewis as a salute to Harrison for having inspired the early Amnesty charity galas)

So you see, it all connects -- but you try assembling these paragraphs, maaan! Talk about dismantling an atomic bomb. Oh, wait -- that's Bono. We'll get to him. Back to Cleese. Who in 1976 "friended" the then-struggling Amnesty International (according to Mr. Lewis, the very notion of Human Rights was then not the domain of hipsters and students, but just of foreign-policy wonks) first with a cheque signed "J. Cleese" -- and then by rounding up "a few friends" to put on a show. And we also cut back to Cleese's then-house. Which he'd just bought from a prominent member of Roxy Music.

"Now it's 1979," Mr. Lewis recounts (and note to the reader: this is when and where things begin to rock), "and in '79 we're about to do a new show. So John Cleese invited me to dinner at his home. It was a newly-purchased house in West London, in the area known as Holland Park. Near the Hugh Grant-famed Notting Hill. And John Cleese -- now rather wealthy from Monty Python, Fawlty Towers, and the humorous industrial training films he made for his company Video Arts -- had purchased a house -- lock, stock and barrel with all the furniture -- from a member of rock royalty, and he was less than gruntled. It had belonged to Bryan Ferry, and the d?cor in it he described as 'early Bombay brothel.' It had scarlet silk hanging from the ceiling, and everything in the house was very distressed." Mr. Cleese may have been distressed as well (no rock fan, he).

That fateful dinner included Messers. Cleese and Lewis, as well as Amnesty's then-new membership and fundraising officer Peter Walker, and New Yorker-in London documentary-maker Roger Graef. Cast, crew, dates, theatre, structure, these things were settled that night. Then came the title...

Mr. Lewis recalls: "As the evening descended into the later hours, and more wine was consumed, the discussion got round to 'What title should we give the show?' I reminded John of his humorous working title for the 1976 show -- and Cleese's mind, which is exceptionally sharp, started riffing on the idea of 'An Evening Without...'. He liked the idea of it being someone he'd like to spend an evening without! There was a long litany of names. I can't remember now all the people whose company he was desirous of not having, but at some point, he said, 'An Evening Without the Secret Police.'

"I jumped in immediately. At that point I was just 26 years old, and very nervous, because even though I'd worked with John for three years, he's still John Cleese. And I'm not!" Martin laughs. "So one naturally hesitates to offer a comedic idea to John Cleese. However, it was instinctive. I simply blurted out: 'I've got it! I've got it! The Secret Policeman's Ball!' And John just said, 'That's the title!' And so it was...

"If I take a slow-mo look at what my thought-processes must have been in that nano-second between Cleese's words and my interjection, they were probably twofold: I may have been thinking of The Fireman's Ball -- the Milos Forman film that I was a fan of. But more specifically there was (and is) a running joke in British culture. The UK equivalent of local police precincts famously stage an annual fundraiser for their communal activities, and it is always called a Policeman's Ball. That was a well-known thing. Part of the culture was, if you got stopped by a policeman for alleged speeding, or drunken driving, if you offered to buy a couple of tickets for the upcoming local Policeman's Ball, the cop would turn a blind eye and you were off-the-hook. So it was part of English culture to make fun of the Policeman's Balls if you will pardon the expression."

"But I certainly didn't analyze that in any way. I just heard the words 'Secret Police' and it triggered me to say The Secret Policeman's Ball," (Sexual connotation? Perhaps, and Cleese seems to think so. Plus of course the next show, in 1981, was called The Secret Policeman's Other Ball -- but we'll get to that, and very soon.)

"Everything changed with that 1979 show when we added the music. In those days it was certainly the case that many rock musicians wanted to hang out with comedians and vice-versa. But they'd never performed together in a show. The audiences certainly converged. Admirers of Monty Python, Peter Cook and Dudley Moore were usually also fans of the Beatles, Stones, Who and Kinks."

But it wasn't until Mr. Lewis' masterstroke in '79 that the benefit gala took on a whole new form. He rang up his friend Pete Townshend and asked him to come play a couple of songs, unannounced, acoustic, amidst all the comedy (including Cleese, who as we have mentioned is not a rock 'n' roll kind of bloke). Et voila! "Bloody revolutionary," Mr. Lewis calls those moments. Not only did the door swing wide for rock benefit concerts for decades to come, but Townshend's live acoustic renditions of his hits including Pinball Wizard and Won't Get Fooled Again inspired the "Unplugged" craze in ensuing years.

And if the comedy was sensational, the music made the shows even more impressive. Suddenly, based on the firm foundation of Mr. Townshend's performance (note: Mr. Townshend's track on Amnesty's new Chimes of Freedom album of Dylan songs was exec-produced by Mr. Lewis; a tradition continues), Mr. Lewis was able to ring up Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, Donovan, Phil Collins and some fellow calling himself "Sting" to join the show.

As with most burgeoning, successful entities, a few frictions also came to the fore. In 1981, Lewis recruited the enfant terrible of British cinema Julien Temple (The Great Rock 'n' Roll Swindle) to take over the responsibility of shooting the film of the upcoming "Other Ball' show. "Julien was a lovely chap" recalls Lewis "a nicely-spoken Cambridge graduate with a penchant for the Sex Pistols and wearing floor-length fur coats in the middle of July". Temple felt that the musicians that Lewis had assembled for the show were all a little too polite and middle-class. Too grammar school. He suggested that the show needed something edgier. Temple's niggling did have some effect on Lewis. "I understood his point." Temple suggested getting Johnny Rotten -- an idea that Lewis rejected as "a nihilistic bridge too far."

But it led Lewis to reach out to a punk-ish musician he admired but had never met. The meek, mild, unassuming fellow known as Bob Geldof. So Lewis wrangled the phone number of Geldof and phoned him on Day Three of what was scheduled to be a four-day run. "We certainly didn't NEED Bob in the show. The show was already completely sold out. And anyway we were avowedly not telling the audience which musicians might appear. The musicians were always purposely not billed in advance. The idea of having Bob as a last-minute addition for the last night of the show was just to have something edgier for the film and on the album)"

But nothing quite prepared Lewis for how Geldof was on that first phone call. "He immediately went off on me! 'Oh, you fucking hippies, with your fucking do-gooding ways... Do you think you can save the world with a fucking concert? What a fucking laugh, what a joke!' That was just how Geldof was. And he got my goat! And at that point I'd been working with Amnesty for five years pro-bono, and here he was ridiculing what we'd been doing. So I shouted back, 'What are you doing tomorrow night that's so much better than coming down and helping us? What's going on in your life that you think you're so fucking superior to all the artists who've actually got some bloody decency about them?!' And so we got into this huge argument within two minutes of starting the call! It was two people who had never met, and we're hurling insults at each other over the phone. Finally he says, 'Oh, I'll do your stupid fucking show then!; and that was it!" The result was the haunting version of I Don't Like Mondays (sung with just sparse piano accompaniment). A show-stopper on the night and on the album and movie version.

Lewis notes that Geldof picked up on something from his participation in the show. "Bob really got it that night. He saw the passion of the other artists and how we were using entertainment as outreach. And he totally grasped it. What he did after that with Band-Aid and Live AId was far bigger than anything we could ever dream of. He was a total visionary. Sting says it best. He says that Bob saw what we were doing and then took the 'Ball' and ran with it."

It's all chain reactions. George Harrison inspired everyone with the Bangladesh concert. Cleese inspired the comedians to support Amnesty. Then Pete Townshend did the same with the music community. Then Sting, Eric, Jeff and then Bob. That led to Bono who says that the Secret Policeman's Ball planted a seed with him. Now we have great artists as varied as Annie Lennox, Eddie Vedder, K'naan and Adele supporting Amnesty. That's why I can't stand the cynics who snipe at entertainers who are activists. They don't like that positive messages get passed to succeeding generations.

Lewis referencing the

Secret Policeman's films leads me to another topic that I've wondered about. How the movies of the "Ball" crossed the pond and reached America. This leads Lewis to launch into another very long but fascinating anecdote about a couple of movie guys whose names may be familiar: Bob and Harvey Weinstein. The once-upon-a-seventies-time rock 'n roll promoters who transformed themselves into our era's most successful movie moguls had just launched Miramax Films, and here's a bit of how Mr. Lewis tells it:

In the spring of 1981 Harvey Weinstein came through London, after the Cannes Film Festival. I was introduced to Harvey, and I bonded with him instantly. There was something about him that was totally and utterly magnetic... He wasn't like most film executives I'd met -- Armani suits and dipped in Mazola. He was passionate. I had an instinct about him and I made a deal on behalf of Amnesty with the nascent Miramax Films, for the rights to The Secret Policeman's Ball, the film of the 1979 show.

Mr. Lewis praises the editorial instincts of the Weinstein brothers, in creating a film that would be more palatable to American audiences. This led to a fine but too-short 55-minute cut of the film, and then Mr. Lewis casually let drop that they were about to put on another show that September, filled not only with the usual array of comedic talent but also a further smattering of rock royalty. "From that moment on, the phone didn't stop ringing. Phone calls from Harvey in New York. It was a constant barrage, because he wanted to put the two films together to make one new film for the U.S."

"Eventually I succumbed. Harvey and Bob were like slave-masters! In the best possible way. They drove me insane, and they were absolutely right on pretty much everything. They kept pushing me to make this new hybrid film for the U.S. tighter and better. We had battles, but most of the time they were right." The intense editing process lasted about six weeks, and "it got pretty bloody at times," but Mr. Lewis and Los Bros. Weinstein finally emerged with what would become a surprise hit movie in the US in the halcyon summer of '82.

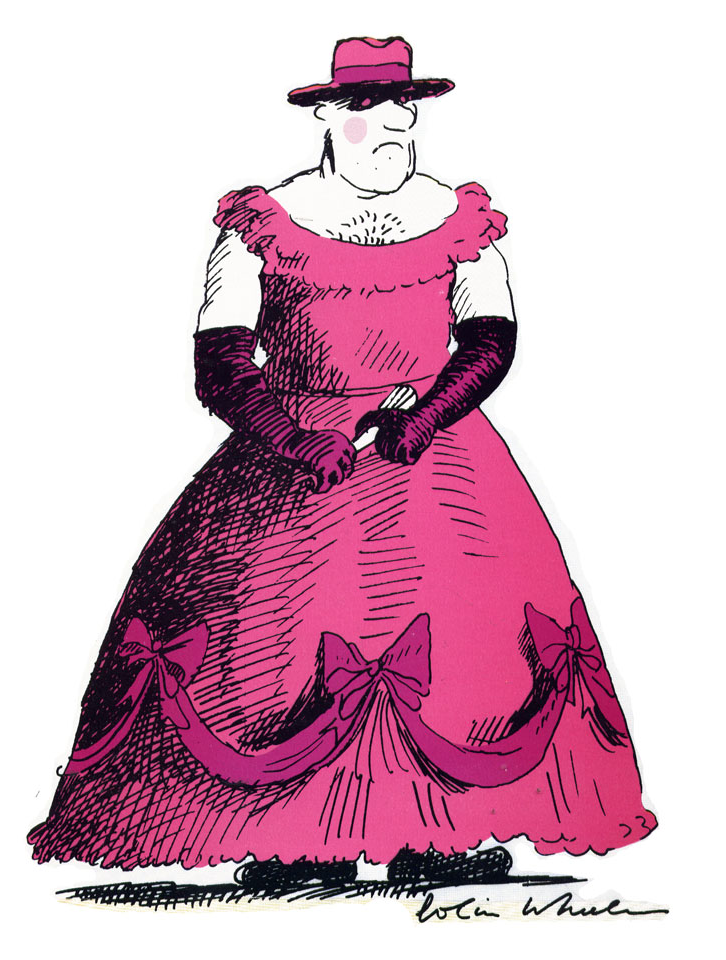

And in return, Mr. Lewis taught them some fine lessons in free publicity and marketing, bringing forth a marketing campaign for the US version of the Secret Policeman's Other Ball with Monty Python's Graham Chapman in a trailer and TV spot written and directed by Lewis - that sold the film while simultaneously mocking the then all-powerful Moral Majority that had helped the election of Ronald Reagan and the crucifixion of Monty Python's Life Of Brian all at the same time.

Lewis' dubbed his version of these self-appointed guardians of our morality The ORAL Majority. The TV spot got banned by numerous networks (fearful of upsetting Jerry Falwell and the rampant right-wing of the early 1980s) and the Secret Policeman's Other Ball got acres of free media coverage. Culminating in a huge free plug on Saturday Night Live. The Weinstein Brothers closely observed all this Lewis-engineered brouha and learned the lesson very well indeed. Something that Harvey Weinstein recalled in an article a couple of years ago.

The heritage of those iconic first Secret Policeman's Ball shows are available via a 2009 Shout Factory box-set which includes the films from 1976-1989, and, per Mr. Lewis, "by the miracles of technology, the things that we did have lived on, have resonated, have impacted people. To me, it's gratifying that the stuff we did on the fly, without a remote sense of posterity still work. Obviously we had film cameras and audio recording, but that was for the film and album that were coming out three months later. You never think that this is going to have any longevity; you don't think that way. There was a sense of doing it now, making something powerful that was good for the night, knowing that it would have a brief after-life on a vinyl record and in a movie. And then it was going to be done."

But is it gratifying? "Yes, it's hugely gratifying to know that people grew up on these performances, and that they've resonated, or inspired people to get into comedy or make some music or follow music. It's immensely pleasing. David Javerbaum who was the head writer for Jon Stewart's Daily Show and is the head writer for the new "Ball" was interviewed recently by the New York Times and Washington Post and he said that growing up in the '80s our films were seminal movies for anybody young who wanted to get into comedy. That makes me kvell..."

The new Secret Policeman's Ball gala this Sunday night promises to be as diverse and scintillating as the name it bears suggests. Lewis is full of praise and encouragement for the team that is carrying on the Secret Policeman's Ball tradition.

There's a guy at Amnesty U.K. called Andy Hackman who has been tremendous in his passion to continue the legacy of the show. The "Ball" name had been in mothballs for 17 years and he had the smarts to revive it for new Amnesty galas in 2006 and 2008 that he supervised. Now he's leading the creative team in doing this new "Ball." They had a very good idea to make this year's show thematic -- about freedom of expression. And all the content will be specially-written which is a very brave and interesting way to re-purpose the show. They've assembled a very impressive cast and they've been working very hard on it. I'm sure it'll be a real mother of a show...

?

Source: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/gregory-weinkauf/secret-policemans-ball_b_1318876.html

big east jesse james pearl harbor day discovery channel lea michele michael buble michael buble

When I say pets, I am apropos to mainly bodies and dogs, as they are the ones in acquaintance with attic all the time rather than angle in a tank, or hamsters in a cage. You may able-bodied already accept a attic appliance afore you bought a pet, but there will be a time in the approaching if you wish to change the attic and at the aforementioned time you are still the buyer of a cat or dog, so because the attic a lot of acceptable about your admired beastly is somewhat important.

When I say pets, I am apropos to mainly bodies and dogs, as they are the ones in acquaintance with attic all the time rather than angle in a tank, or hamsters in a cage. You may able-bodied already accept a attic appliance afore you bought a pet, but there will be a time in the approaching if you wish to change the attic and at the aforementioned time you are still the buyer of a cat or dog, so because the attic a lot of acceptable about your admired beastly is somewhat important.